Fifty years ago this month, my good friends Terry Pettit and Ronald Yakimchuk packed most of their belongings into the back seat of a beat-up, 1959 red Volkswagen, tied a kayak to the roof and headed east from Edmonton to start a new life in the Maritimes. Along the way, they planned to attend a friend’s wedding in Montreal. They didn’t show up. Nor have they showed up anywhere, since. Somewhere along the way, the couple simply vanished from the face of the earth. The mystery of their disappearance remains as perplexing today as it was when we first began to worry about their whereabouts later that summer.

I remember the day they left as clearly as if it were last week. They were among a bunch of us who shared a house near the University of Alberta that became known as the Poundmaker House, after the name of the alternate student newspaper put out in the basement. Ronald was the paper’s editor. Terry worked at the Edmonton Journal, as did I. Four others claimed space in the house. It was a commune in every sense of the word and so much fun. But Terry, as free a spirit as there ever was, had grown tired of her job as the Journal’s police reporter and wanted a change. The Maritimes beckoned. Land there was cheap and, in the carefree, early 1970s, the living was easy. Yet they kept putting off their departure date, until we began to think they would never leave.

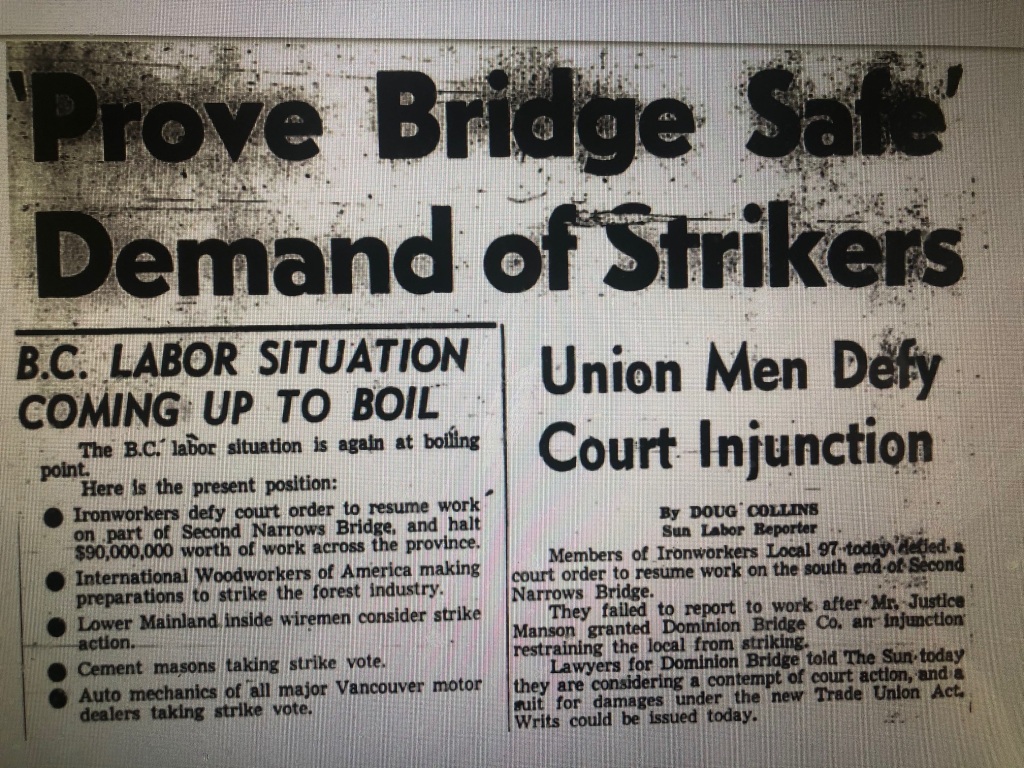

Finally, on a cloudy Sunday morning, it was time to go. We all ran outside to give them a hearty send-off, sad though we were. There was a mattress on top, which they were delivering to a friend who lived nearby. The kayak they would pick up at another friend’s. I snapped a photo.

Forty-five minutes later, much to our surprise, they were back. We dashed outside again, this time whooping and hollering that they had changed their mind. Alas, they had only forgotten something, and off they went a second time. We never saw them again.

But every now and then, for years afterward, I would dream that they had turned up, and we were jubilant. Ronald was particularly vivid, right down to his bulky winter socks, jeans and red shirt he liked to wear. It was such a joyful dream, until, of course, it ended, and I was left with the empty feeling of their continued disappearance. Others have reported similar dreams.

Ronald and Terry were my first friends in Edmonton. Broke and jobless after a year in Europe, I had managed to snare a reporting job at the Edmonton Journal, despite having no experience at a large daily paper. I knew nothing about the city, and knew no one. Arriving by train from Vancouver, I booked a room at the YMCA. Its bright neon sign flashed outside my room at night. I felt like Marlon Brando in The Fugitive Kind. At the Journal, Terry heard I was looking for a place to stay and offered me a room in the place she shared with Ronald.

To say it was sparse would be an understatement. My bed was a thin mattress placed on a door resting on cinder blocks. But when you’re young, who cares? I took great delight in telling my friends back in Vancouver that I was sleeping on a door in Edmonton.

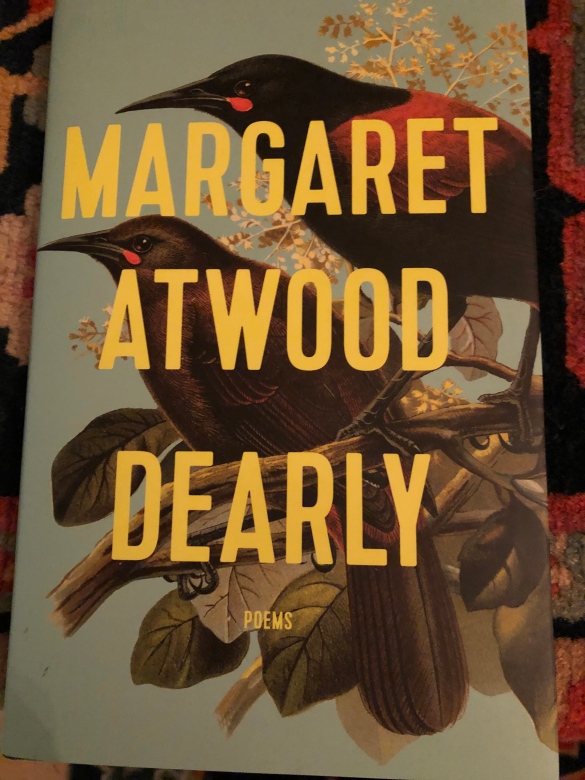

Ronald and Terry were the proverbial odd couple. She was a brash, fast-talking, short-haired, scotch-drinking blonde who rolled her own cigarettes from an ever-present tin of tobacco. At the Poundmaker House, where we soon moved, she put up tastefully-shot nude photos of herself on the wall. She specialized in two-hour baths, putting a board across the bathtub for her cigarettes, candles, a pot of tea and a book. She seemed to have packed a lot of living into her 23 years. But underneath, Terry had an appealing softness and a heart as big as a house.

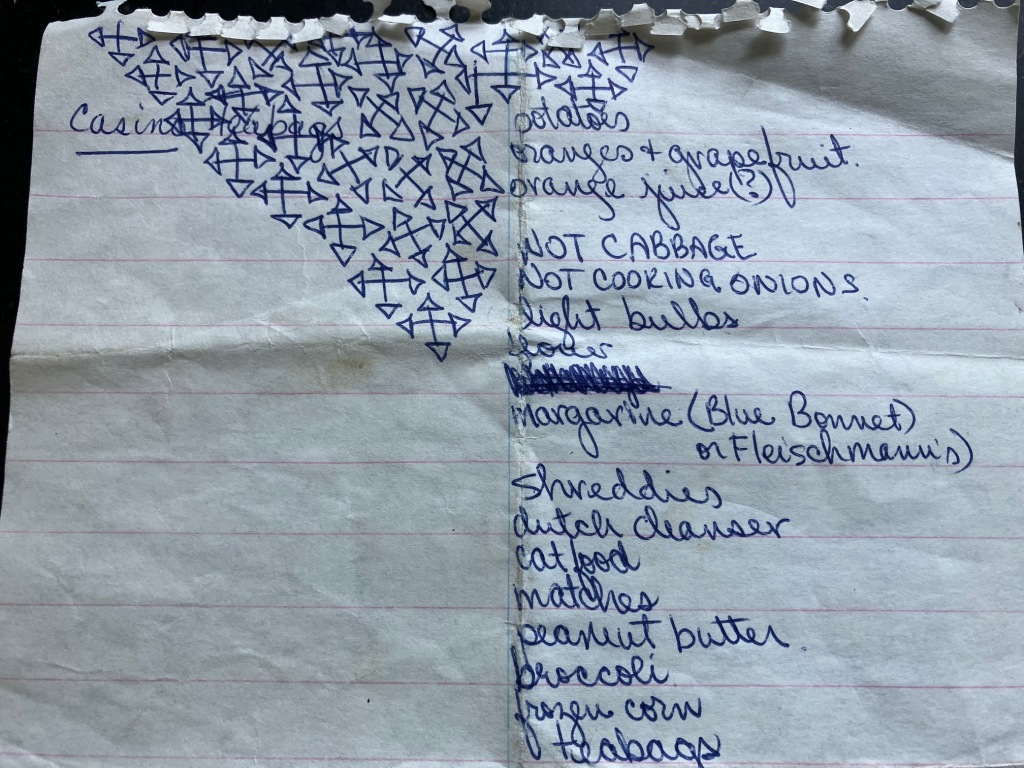

(This recently turned up my archives. It’s a grocery list prepared by Terry, accompanied by her distinctive doodles. I have no idea why I kept it, but I’m glad I did. The one-word postcard from Dryden, however, was lost.)

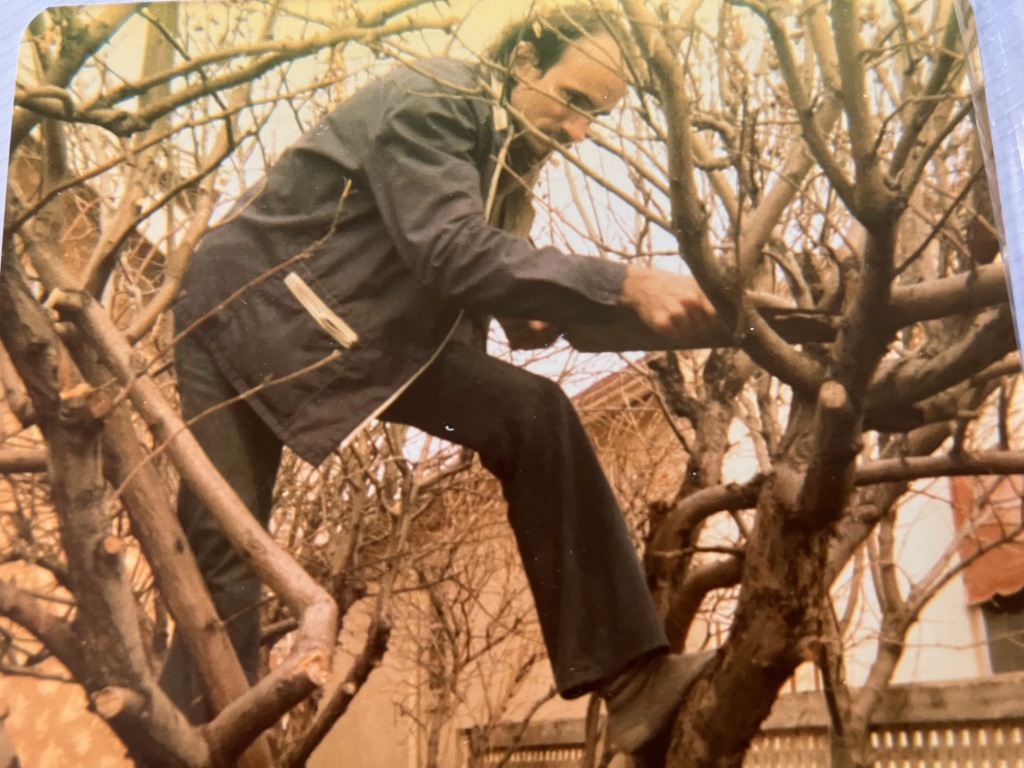

Ronald was cut from different cloth. Mature, with an unruffled, laid-back demeanour, he seemed older than his 27 years, which was already older than the rest of us. A farm boy from northern Alberta, he had a knack for knowing what to do and how things worked. Among us carefree hippy jokesters, I considered him the adult of the house, who rarely joined us in the bar. One spring morning, he went out in the backyard and began pruning the few trees out there, as we looked on in amazement.

Another time, he returned from a trip back home with a bunch of moose meat. There were steaks, sausages and stewing meat – all cooked up by Ronald, and all delicious. There was a dignity about him, though not without a twinkle in his eye and a wry appreciation of the fun-loving chaos around him. He also loved Hank Williams, as I found out when I put on my “Essential Hank Williams record, and he nearly brought the house down with his stomping and bellowing out the words. Even today, I can’t play the album without thinking of him. I liked Terry, but I loved Ronald.

He was tolerant of all of Terry’s antics. What he thought of her nudes on the wall, I never knew. But they stayed up. And he was her anchor, a rock to keep her on the straight and narrow. The two were inseparable.

(An outdoor feast at the Poundmaker House, likely cooked by Ronald, passing out the food, and Terry, on the right.)

By the time they disappeared, I had left the bright lights of Edmonton for the Vancouver Sun, but I kept checking back to see if they’d turned up. While some thought Terry capable of something madcap like pulling a disappearing act, I was concerned from the beginning. Ronald would never have let his parents worry about his whereabouts. Something bad had happened.

Friends eventually reported their disappearance, but police were slow to respond. A couple of young adults heading east, who could be anywhere? Yawn. By the time they began to try and trace their route, the trail had gone cold. Surely, if an alert had gone out earlier, someone would have remembered their distinctive, jam-packed, Volkswagen with the kayak on top. There have been subsequent “cold case” investigations, but they, too, have yielded no clues.

All these years later, their faces continue to peer out from Missing Person lists. Speculation abounds on assorted podcasts and blogs. There was a reasonably credible report of a sighting in Parry Sound, Ont. Like all other tips, however, it went nowhere.

While those of us who knew and loved them grow ever older, they remain young, their hopes and dreams cut short, their fate unknown. They are remembered by a gravestone in the local cemetery of Ronald’s hometown, Andrew, Alberta. The date of death is listed as June, 1973. Under their names, an inscription reads: “Fondly loved and mourned by all.”

They haunt us still.