Like many, I knew the works of Alex Colville almost entirely from the ubiquitous reproductions of his most well-known paintings. The blonde woman on the PEI ferry staring out with her powerful binoculars at who-knows-what. The haunting image of a large horse galloping down the tracks towards an approaching train, its searchlight probing the darkness. (I first saw that one on the cover of Bruce Cockburn’s wonderful album, Night Vision.) An early painting that perfectly captured the long march of worn-out Canadian infantry through the snowy, flooded flatlands of Holland. And a few other depictions of meticulous “frozen in time” moments that were Colville’s trademark. Frankly, I didn’t think that much of him as an artist, archly regarding him as someone having more of a shtick than touched by the sublime.

Not for the first time, how wrong I was. The recently-concluded Colville show at the Art Gallery of Ontario, which I managed to take in on Boxing Day, blew me away. It showed once again the advantage of representing an artist’s full career, with more than a hundred paintings, most of which I’d never seen before. They were coupled with perceptive analysis by the curators, short, accessible interviews with the artist on video, and some interesting links to other examples of popular culture. I came away with a totally new appreciation of this great Canadian artist. (And, as my friend Gord pointed out, it also reminded him not to paint a nude picture of himself at the age of 80, as Colville did, unashamedly.)

Alex Colville was true to his vision all his life. He didn’t get caught up in fads, nor was he influenced by the zillions paid to “artists” for splashing around paint and polka dots. One of his late paintings didn’t look that much different from something he painted in his 40’s. Colville lived in small town New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, and those are the scenes he focused on, with his famous meticulous attention to detail. As he explained: “Only by living in a little place for a long time can one build up a sort of extensive body of complex knowledge and understanding of what goes on.”

The curators make an insightful linkage with another great Canadian artist of small town life, Alice Munro. Indeed, and this was new to me, that graphic, stunted elm tree on the cover of one of Munro’s best short story collections, The Progress of Love, was a painting by Colville. Critic Amy Lavender’s excellent perspective of the similarities and differences between the two is included in the show. http://www.welcometocolville.ca/home-from-away

The curators make an insightful linkage with another great Canadian artist of small town life, Alice Munro. Indeed, and this was new to me, that graphic, stunted elm tree on the cover of one of Munro’s best short story collections, The Progress of Love, was a painting by Colville. Critic Amy Lavender’s excellent perspective of the similarities and differences between the two is included in the show. http://www.welcometocolville.ca/home-from-away

As she observes, Colville was gentler to his subjects and small town life than was Munro.

But not always. I was surprised to see the prominence of guns in several of his paintings, often without explanation, as if some sort of violence were just around the corner. And, even without guns, there is often a hint of something disturbing

But not always. I was surprised to see the prominence of guns in several of his paintings, often without explanation, as if some sort of violence were just around the corner. And, even without guns, there is often a hint of something disturbing  about the outwardly simple scene he portrays on canvas. The more you stare at these powerful paintings, the more menacing they seem. I was particularly taken by a painting I hadn’t seen before, January (1971), which depict a couple out snowshoeing. The man, in a hooded parka and sunglasses, stares straight ahead. He looks angry. His companion, a ways behind him, looks nervously over her shoulder at something or someone unseen. Disconcerting, to say the least, and open to a multitude of interpretations.

about the outwardly simple scene he portrays on canvas. The more you stare at these powerful paintings, the more menacing they seem. I was particularly taken by a painting I hadn’t seen before, January (1971), which depict a couple out snowshoeing. The man, in a hooded parka and sunglasses, stares straight ahead. He looks angry. His companion, a ways behind him, looks nervously over her shoulder at something or someone unseen. Disconcerting, to say the least, and open to a multitude of interpretations.

Meanwhile, Stanley Kubrick’s famous fright film, The Shining, has not one but four Colville paintings on the walls in various creepy scenes. The AGO helpfully lists what appears when in the movie: Woman and Terrier, 10:57; Horse and Train (of course), 14:31; Dog, Boy, and St. John River, 58.30; Moon and Cow, 2:09:32. See it again!

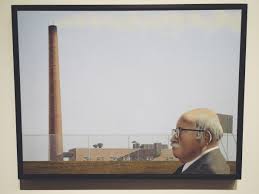

Here’s some other stuff I learned. Colville designed the special Centennial coins (remember the rabbit?). A scene in Moonrise Kingdom is almost a straight steal from Colville’s famous binoculars painting. Because life is forever stranger than fiction, when Colville showed a neighbour, a professor, a painting he had made of him out for a walk, the we are told that the neighbour recoiled. He had lost his family to the Holocaust and prominent in the background of Colville’s painting was a large smokestack.

Here’s some other stuff I learned. Colville designed the special Centennial coins (remember the rabbit?). A scene in Moonrise Kingdom is almost a straight steal from Colville’s famous binoculars painting. Because life is forever stranger than fiction, when Colville showed a neighbour, a professor, a painting he had made of him out for a walk, the we are told that the neighbour recoiled. He had lost his family to the Holocaust and prominent in the background of Colville’s painting was a large smokestack.

And I had no idea of the shocking calamity that struck Rhoda Colville, the artist’s wife and muse for 70 years. Just eight years old, she lost her father, sister, brother, grandfather and an aunt in one fell swoop, when their car collided with a train, killing all five. We first come across the tragedy in an otherwise light-hearted comic book on Rhoda’s life more than halfway through the exhibit, tucked away in an obscure display corner.

One wonders how Colville might have turned out, but for his long, loving relationship with Rhoda. She is depicted in so many of his paintings, from the young quizzical woman on the PEI ferry to the aging woman in her eighties, straining to clip her toenails. It was a true love match, that began when the shy, young Colville took her hand as they crossed a street in Sackville, when both were students at Mount Allison University. There is a charming interview with Rhoda in the show in which she recounts that pivotal moment. Six decades later, her face still lit up at the memory. “That’s when our friendship became something more.”

I rarely remember an exhibition so absorbing. Almost every painting commanded attention. No wonder it was the 10th-most attended exhibition in the history of the AGO, with the highest ever for a show featuring Canadian art. The Colville retrospective moves to the National Art Gallery in Ottawa on April 23. If you’re in the ‘hood, it’s a must.